Search

Summary

Loading AI-generated summary based on World History Encyclopedia articles ...

Search Results

Article

Ancient Israelite & Judean Religion

As early as the 10th century BCE, Israelite and Judean religion began to emerge within the broader West Semitic culture, otherwise known as Canaanite culture. Between the 10th century and 7th centuries BCE, ancient Israelite and Judean religion...

Definition

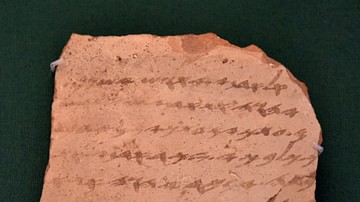

Ancient Israelite Art

Ancient Israelite art traditions are evident especially on stamps seals, ivories from Samaria, and carvings, each with motifs connecting it to more general artistic traditions throughout the Levant. Ancient Israel, and therefore its art...

Definition

Ancient Judean Technology

Though the kingdom of Judah was not particularly notable in terms of technological developments, technology, nonetheless, played a central role in its rise as a political power in the region. Emerging in the 10th century BCE, it reached its...

Article

Early Judaism

During the period of early Judaism (6th century BCE - 70 CE), Judean religion began to develop ideas which diverged significantly from 10th-to-7th-centuries BCE Israelite and Judean religion. In particular, this period marks a significant...

Definition

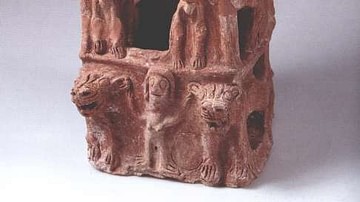

Judean Pillar Figurines

Judean pillar figurines are an interesting and specific form of female representation from the Iron Age kingdom of Judah. They fall into a broader category of pillar figurines, which have a pole-like lower body and have been found throughout...

Definition

Ancient Israelite Technology

Technology enabled ancient Israel, the Northern Kingdom excluding Judah, to be economically prosperous and establish itself as a major political power as early as the 10th century BCE, steadily growing until its destruction in 720 BCE. Some...

Definition

Religion in the Ancient World

Religion (from the Latin Religio, meaning 'restraint,' or Relegere, according to Cicero, meaning 'to repeat, to read again,' or, most likely, Religionem, 'to show respect for what is sacred') is an organized system of beliefs and practices...

Article

Ethnicity & Identity Within the Four-Room House

The process of determining ethnicity is a problematic venture, even more so when interpreted through the archaeological record. Despite this issue, evidence, such as the four-room house, has been preserved that can be interpreted to represent...

Definition

Ancient Persian Religion

Ancient Persian religion was a polytheistic faith which corresponds roughly to what is known today as ancient Persian mythology. It first developed in the region known as Greater Iran (the Caucasus, Central Asia, South Asia, and West Asia...

Article

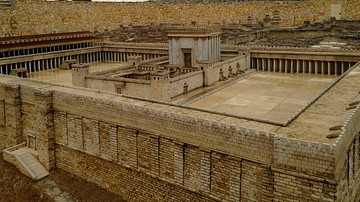

The Ancient Synagogue in Israel & the Diaspora

A unique and fundamental aspect of ancient Judean society in both Israel and the Diaspora, the ancient synagogue represents an inclusive, localized form of worship that did not crystallize until the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. In...